This writing has placed strong emphasis on how resources are linked to the health of a society and its economy, first with how resource scarcity inevitably causes economic hardship and thus conflict, and second, how we can use technology to fundamentally prevent that problem from occurring.

Yet while the scarcity of resources carries negative economic impact, an abundance of resources inversely causes economic growth – all the more so if that abundance is indefinite. To fully embrace that growth, this writing advocates for spending significant sums of money to build systems on a nationwide scale to make unlimited energy and resources a reality.

The model that this expenditure operates is neither capitalism, socialism nor even “social democracy” – an oft-referenced capitalist/social hybrid that’s seen in many European democracies. Rather, this model takes a wholly distinct approach to a society’s economic framework because it establishes parameters outside of a finite resource paradigm.

This model is called “Collective Capitalism” because it hinges on the belief that the systems of capitalism work best when all social sectors are operating from a place of maximum strength. This idea in and of itself is not controversial – few would argue that a collectively stronger, more educated, more prosperous and more healthy society functions at greater performance than not. Yet using an ideological approach (liberal, conservative, theological ) to achieve this status is far more elusive than a technological approach that can help build the foundations by tangible means of indefinite provision. Indeed, it’s much easier to provide water, energy, food or fuel to everyone when you can synthesize them inexpensively to effectively unlimited scales.

But the core resource provisions for our social operation are simply the first step. Collective Capitalism, as a mindset, seeks to extend those provisions to everyone at a low cost so everyone, collectively, can operate from a place of security and strength and engage the mechanisms of capitalism to invest, achieve, discover, invent and, in turn, continue to perpetually improve the collective by virtue of capitalism’s inherent rewards. It’s the system we should have had, and wish we had, but was missing the key component of unlimited energy and resources.

For example, here are some of the more noteworthy aspects of social and economic improvement that can be realized through Scarcity Zero:

More Disposable Income

According to the U.S. Census, the median household income in the United States is $60,336.[1] Not accounting for state and local sales taxes (as well as property taxes if a homeowner and/or extra payroll taxes if self-employed), the average wage earner has a tax burden of 29.6% of their 2018 pre-tax income.[2] That would mean that the median U.S. household takes home roughly $42,500 (rounding up for easier math).

That comes to $816.30 per week, or $3,541.66 per month.

With that broken down, we’ll source some routine life costs:

- According to the USDA (as cited by USA Today), the weekly cost to feed a family of four ranges from $146-$289.00.[4] The median cost of that range is $218.00 / week. That’s $942.50 per month, or $11,310 per year.

- According to the American Automobile Association (AAA) using data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, fuel costs average approximately 11.6 cents per mile,[4] and the average American adult drives roughly 13,476 miles per year.[5] Assuming each household of four includes two working parents with two vehicles, that’s 26,476 miles driven per year at a fuel cost of $3,071 per year.

- As of 2017, the average U.S. household consumes roughly 10,400 kilowatt-hours of electricity per year (as of 2018, it’s 10,972).[6] While the average national price of electricity is 10.53 cents per kilowatt-hour for all sectors, it’s averages 12.87 cents for households[7] with a contiguous high of 20.60 cents for New England and a national high of 32.47 cents for Hawaii. That comes to an average of $1,155.35 nationally, although New England and Hawaii are two to three times that.

- According to Rocket Mortgage, a subsidiary of Quicken Loans, the average natural gas bill is $661 per year ($55/month).[8] The company further estimates that the average water bill is roughly $845 per year ($70.39/month) for households consuming the national average of 88 gallons per day.[9] That comes to a total of $1,506 per year.

Adding up the costs of electricity, fuel, water and heat, that comes to $5,732 per year, arriving at $17,042 when the cost of food is added in.

If we were to assume a reduction in the cost of electricity, fuel, water and heat to correspond with Scarcity Zero’s target reduction of 83% to 2 cents per kilowatt-hour, that would present a cost savings of $4,757 per year. Let’s assume further that these cost reductions translated to food in the form of reduced energy / resource costs for irrigation, cultivation and transportation, as well as the advent of vertical farming within urban infrastructure powered by inexpensive energy. If we were to suggest a 30% reduction in food cost, that would come to a cost savings of $3,393 per year. Added to the savings from utilities, and that derives a sum of some $8,150 per year for family of four.

Assuming further that this cost saving could be extrapolated on a per-capita basis, that comes to a total of $2,037 per person of any age. Across a society of 330 million (according to the U.S. census), that comes to a total of $672 billion that can be injected into our economy, saved for retirement or education, invested into real estate, businesses or other financial strategies.

Across our society, that translates to $6.72 trillion per decade.

The scale of such a figure presents massive implications for all income classes, but especially the lowest – for each extra dollar in their pocket in this context is not only tax-free (effectively making its real value 29% higher), it functions as a force multiplier to their financial mobility. Indeed, an extra $500 per month to a family living paycheck to paycheck matters far more than it does to a family that’s independently wealthy.

Yet in this application, the distribution isn’t necessarily weighted to certain economic classes – everyone gets the same bonus based on reduced costs society-wide. It’s not socialism that takes from the wealthy to give to the poor, it simply uses technology to raise the collective floor.

Reduced Business Costs

Energy is an inexorable aspect of the costs of doing business today in our global economy. This is quantified across several key areas: energy costs of material and/or resource procurement, manufacturing, transportation, processing of both material and data, heating, lighting, etc. These factors each manifest one way or another into nearly all business sectors, and consequently are absorbed into the price of the product or service that’s offered at market. If reduced energy costs can provide a cost savings for residential households, the purchasing and consumption scale of incorporated business would see corresponding reductions on subsequently higher orders.

This is all the truer since the cost reductions would cascade across an array of business sectors and their interoperating supply and manufacturing chains. For example: if Scarcity Zero makes a raw material 20% less expensive to source at equal quality, reduces the energy cost to manufacture systems with it by 20%, and further enables a 20% cost reduction to transport the manufactured product to market – those cost savings combine across the supply chain. Across our national – or global – economy, the financial implications are enormous.

To determine just how impactful, we’ll take a look at figures from the Energy Information Administration, specifically their Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) for the year 2012 (the last year in which full data is available).[10]

According to the survey, American business consumed a total of 1.243 trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity.[11] At a national average cost of 10.67 cents per kilowatt-hour for commercial enterprise and 6.92 cents per kilowatt-hour for industrial applications (heavy manufacturing),[12] that respectively totals $132.63 billion and $86 billion.

The CBECS survey further assessed that American business consumed 2.193 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in 2012[13] at a cost of $7.78 per thousand cubic feet for commercial enterprise and $4.21 per thousand cubic feet for industrial applications. That respectively totals $17 billion and $9.23 billion.

Now, we’ll take a quick look at fuel. According to the Department of Transportation, commercial vehicles (including trucks and busses) accounted for about ten percent of all vehicle miles driven.[14] Further data by the Energy Information Administration, as curated by Statista, estimates that the U.S. consumed 8.98 million barrels per day of gasoline and 3.13 million barrels per day of distillate fuel oil (which includes diesel).[15] That translates to 3.277 billion barrels of gasoline and 1.142 billion barrels of distillate fuel oil. Extrapolated into gallons (at 42 gallons to the barrel), these figures respectively translate to 137.66 billion gallons of gasoline and 47.98 billion gallons of diesel.

Leveraging the Department of Transportation’s estimate, we’ll assume that 10% of that gasoline consumption was from commercial and industrial applications. Yet since diesel is the fuel of choice for trucking and heavy machinery, we’ll assume 95% of diesel consumption came from commercial and industrial enterprise. This leaves a figure of 13.77 billion gallons of gasoline and 45.58 billion gallons of diesel that can be attributed to businesses.

At a national average price of $2.70 / gallon for gasoline and $3.06 for diesel,[16] that comes to a total aggregate cost of $176.65 billion.

With this established, let’s add up our totals. Based on the calculations above, we’ve estimated that:

- American commercial enterprises annually spend $132.63 billion on electricity, falling to $86 billion for heavy industry.

- American commercial enterprises annually spend $17 billion on natural gas, falling to $9.23 billion for heavy industry.

Added up, that comes to $149.63 billion for commercial enterprises and $95.23 billion for heavy industry that’s added on top of the estimated $176.65 billion shared by both for diesel and fuel costs.

This creates a total cost liability of between $326.28 billion and $271.88 billion depending on commercial or industrial application. If we were to split the difference, that would come to a figure of roughly $300 billion per year.

If that figure, for sake of argument, were subjected to an 82% cost reduction, that would present a cost savings of $246 billion per year. As this translates to $2.46 trillion per decade, such cost reductions present a capital abundance that can further enable businesses of all sizes to invest in their own growth and future success.

This approach can be scaled further through targeted tax incentives. When discussing Scarcity Zero’s management and implementation strategy in the previous section of the Appendix, mention was made of the possibility of dramatically lowering the tax liability for businesses operating in Scarcity Zero’s sectors, along with corresponding incentives for the employees and investors of such companies.

This is a key component of a “Collective Capitalism” mindset, hinging on the notion that industries and personnel that provide critical – and extremely beneficial – services to society’s long-term operation and improvement should face a correspondingly reduced tax liability to fund society’s public functions. It defies reason that a company making cigarettes or hawking payday loans at predatory interest rates should operate under the same tax burden as companies developing energy technologies for The Public Interest Company, growing food in vertical farms or building next-generation infrastructure to provide an improved quality of life for society.

The same is true for the employees of such industries, as well as their investors across equities, bonds and other financial products. If an industry provides empirical social benefits on a transformational scale, why should an employee face the same tax burden as an employee of an industry that doesn’t directly deliver the same degree of social improvements? Further, why should an investor seeking to inject capital into a socially beneficial enterprise pay the same capital gains taxes as someone seeking a quick profit by shorting the same stock, or by throwing their money into shadier organizations like private prisons or conglomerates with abysmal human rights records?

Here’s what this could look like in practice. Let’s say that we establish an empirical threshold (defined specifics, not abstract opinions) of social benefit within varied industrial sectors, and assign “classifications” to such industries using a transparent assessment criteria. Beyond participation in Scarcity Zero, this criteria could include a lower ratio of executive to average worker compensation, demonstrated ethical track record, external social outreach and investment, operational transparency, and/or quality of benefits offered to their workforce in aggregate.

Based on this corporate classification (not unlike a “B-Corp” designation), the company, its employees, and its investors could enjoy special tax incentives. An example might reflect the following table:

| Corporate Classification | Corporate Income Tax Rate | Capital Gains Tax Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Class A Corporation | 0-5% on a progressive scale based on income. Maximum tax rate is 5%. Employee income tax is capped at 15% up to $1M. |

Short term: 5%. Long term: 0%. After $1M, gains are taxed as income. |

| Class B Corporation | 0-10% on a progressive scale based on income. Maximum tax rate is 10%. Employee income tax is capped at 20%, up to $1M. | Short term: 15%. Long term: 5%. After $1M, gains are taxed as income. |

| Class C Corporation (Current Tax Rates as of 2019) |

0-21% on a progressive scale based on income. Maximum tax rate is 21%. Employee income tax rate unchanged. | Short term: 25%. Long term: 15%. After $1M, gains are taxed as income. |

Under this model, current companies do not pay any more in taxation than they do today, yet Class A and Class B corporations would receive significantly more attractive tax incentives to engage in business sectors earning such classifications – of which Scarcity Zero would be a primary qualifier. This reasoning can extend further to other industries that deliver an empirical social benefit: making bionic limbs for amputees, investing in next-generation medical research, building advanced transportation infrastructure, and so on.

In such reasoning, there is a clear distinction here between “picking winners and losers” and incentivizing investment and patronage to industries that make the world an objectively better place. Collective Capitalism doesn’t seek methods that punish industries, companies, or personnel that do not choose to invest in empirical social progress, but it does seek to reward them through the establishment of protocols and frameworks that makes this task easier and less expensive. In turn, this would incentivize and encourage a social impetus to continually invest and be part of industries that deliver a strong social benefit – and, further, seek to expand that benefit at higher rates of return than otherwise.

Consequently, these incentives could see reprioritizations across our economy. Defense contractors, for instance, aren’t really companies that specialize in building high-tech weaponry so much as they are expert engineering firms that specializing in building high-tech systems. There are few obstacles, in real terms, from shifting primary focus from military infrastructure to domestic infrastructure. If you can build a Generation-V fighter jet, you can build effectively anything. Providing both a public funding impetus and tax incentive to shift from weapons to, say, sophisticated energy technologies, next-generation rail travel, hyperloops or civilian aerospace can help facilitate this transition.

In conjunction with lower operating expenses from energy cost reductions and public funding allocations for Scarcity Zero and its underlying technologies, this can keep current flagship industries in play building critical American infrastructure, while also enabling opportunities for start-ups to gain a foothold and accordingly prosper. This would transform the “military industrial complex” into an “energy/resource industrial complex,” delivering cascading social benefits at only moderate costs.

Increased Job Growth

Reducing the operating expenses of businesses, both through drastically lower energy costs and enhanced tax incentives, stands to provide several avenues for job creation beyond the obvious potential presented by large-scale investment in next-generation energy and resource technologies. Remaining competitive in this new frontier will require as much investment in personnel as technology, both in terms of manufacturing, maintenance, marketing, managing and deployment logistics. This means jobs.

It’s true that in the past, certain historical instances of operating cost reductions have seen some companies choose to pay for increased executive bonuses and stock buybacks,[17] as opposed to workforce expansion and salary increases. But these have primarily occurred in instances where a company had entrenched dominance in their market sector and could comfortably afford to rest on their laurels to hold off emergent competitors who came to market with more nimble and disruptive approaches.

This possibility would be substantially harder with the market sectors opened up by Scarcity Zero, not only because the technologies (and thus industries) are in a degree of infancy that hinders monopolization, but also because The Public Interest company (in this model) would seek to prioritize contracts with companies who a) hire American, b) pay competitive wages and benefits, c) competes fairly and refrains from anticompetitive strategies, and d) takes strides to achieve a corporate classification that would only be granted after demonstrating a higher tier of operating ethics both to their society and workforce.

In such instances, the possibilities for job growth are enormous.

To see how, let’s quickly circle back to the estimated $246 billion American businesses would annually save under Scarcity Zero. At an assumed 25% tax overhead to hire a salaried employee at $50,000 per year ($62,500), this reduction in energy and fuel costs alone would be sufficient to create 3.94 million new jobs. Adding on the potential savings due to increased corporate classification, investment in next-generation industries and technologies, and the advent and functions of The Public Interest Company, and the potential job growth increases substantially.

Of the $663 billion congressional appropriation that would be devoted to implementing Scarcity Zero over a 10-year period, it’s essential to note that this money isn’t just sent into a void – it’s paid to enterprises who win contracts to develop and deploy the technologies inherent to Scarcity Zero under a transparent bidding process.

The first area to receive these funds would be engineering companies that develop the underlying technologies for Scarcity Zero. This will create job demand within a multitude of technical skills: physics and engineering, metallurgy, computer science, software development, graphic modelling, automated manufacturing, 3-D printing, quality control, human resources, project management, advertising and marketing (among others).

As these companies expand along with job demand, they in turn will need to expand their acquisition of materials and resources to develop the systems they were contracted to deliver. They will need to buy materials, tools, vehicles, fixtures, office space, uniforms, amenities and everything else that comes from the manufacturing world. All of this will create jobs.

It will also create job demand in industrial sectors these companies depend on to operate, which in turn will create job demand in all of the support and promotion positions that make their own business possible. This job demand will create additional demand for schools and the educators to staff them along with all of the support positions that make their jobs possible. The result is a cascading increase in job demand corresponding to a cascading reduction in operating costs – not only creating a next-generation economy, but also revitalizing the state of American manufacturing to a subsequently higher tier.

Revitalized American Manufacturing

With the exception of advents in information technologies and weapons development, the overall state of American manufacturing has been in decline since the height of post-WWII boom years.[18] While there are myriad causes of this state of affairs, an investment Scarcity Zero enables us to chart a fundamentally different course towards a future where the American economy can reclaim its status as a global leader in technology, infrastructure and innovation.

Sparking a social drive to build advanced energy technologies and corresponding infrastructure gives us the head start on research and development within this new economic frontier. Further, by implementing them first in our country we would become the foremost experts in this sector and those surrounding it. And as we have engineered the technologies therein and have perfected their ideal means of deployment, we position ourselves to be their best purveyors to other countries. The potential size of this market internationally is easily in the trillions of dollars over the long term, as our expertise with these technologies would translate to repeat business in contracts for maintenance, upgrades, etc., providing future revenue streams to American business and our economy.

Reduced Social Afflictions

The social investments and derivative results inherent to Scarcity Zero and Collective Capitalism fundamentally makes life easier and less expensive. An abundance of inexpensive energy and resources reduces the cost of living and increases economic, career and social mobility. It further mitigates the scarcity and desperation-driven impetuses to engage in criminal activity. Life’s just “better” and people have more time and opportunities to engage in activities that they find value in – be it their family, hobbies, side projects or new vocations. In these circumstances, it is significantly easier for someone to start their own company, innovate a new idea or product, and/or invest either time or money in another venture they believe will ultimately have social value. It expands the purchasing power, investing power and financial influence of the middle class, and extends to them luxuries that were once available only to the social elite.

Effectively, Collective Capitalism leads to a world that is powered by resource abundance, a removal of need and a social safety net that is technology-driven, not by limiting the ceiling or redistributing from the top – but rather by using technology to simply raise the floor and the foundations on which it stands.

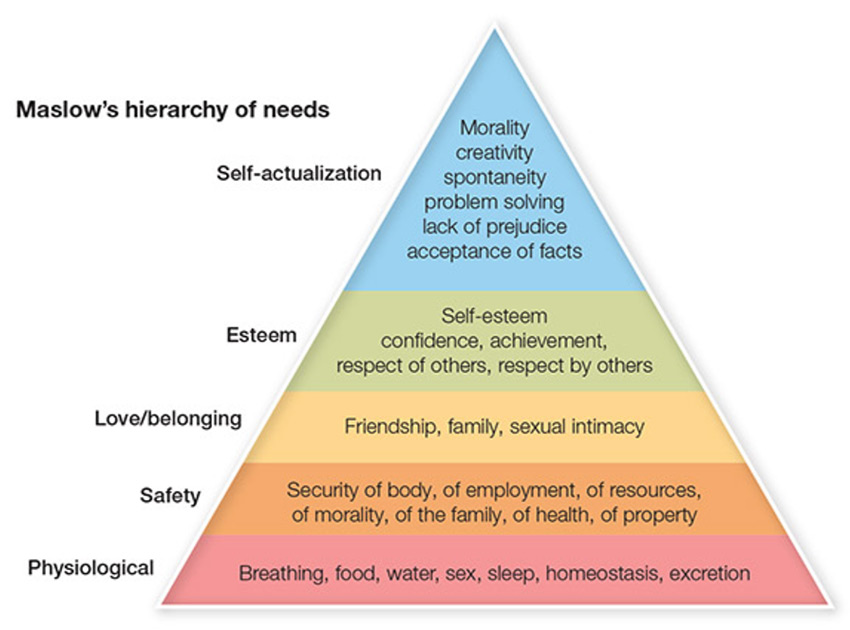

The chart below represents a concept known as “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.” It breaks down the core needs of human beings, with the lower end of the pyramid represented by critical need that is resource-driven – the needs Scarcity Zero provides as a core function. This allows society to place increased focus on the remaining categories of need, encouraging us to extend ourselves for more meaningful things that result in greater social enrichment, culturally, intellectually and spiritually.

In this line of reasoning, it’s worth mentioning that much of our culture today is provided by artists and writers who thrived in generations past. (Indeed, many of the comic book heroes who grace movie screens today debuted 50-80 years ago). There’s little market for today’s storytellers, artists, poets, artisans or philosophers because it’s difficult for them to make a living from doing so. These people once gave society great value, but today their creative capabilities are sidelined by the demands of a cutthroat economy.

The financial benefits inherent to the Collective Capitalism afford the provision for abstract social concepts and enlighten the subjects we discuss, goals we set and behaviors we value. Because all core needs are met in this model through technology, the stresses and efforts that were previously required to meet the demands of life are no longer present. Concordantly, we no longer need to distract ourselves with fleeting content to make ourselves feel better in the face of these stresses and efforts, allowing us to finally concentrate on what we truly want as people, as we truly want it.

Over time, this will further mitigate existing social problems and increase the scale of shared economic prosperity on multiple fronts which allows our society to look inward and mend its wounds to become stronger and form a more cohesive cultural identity based on an improved quality of life.

Notably, this is an identity that can refresh our reputation abroad. When combined with the provision of Scarcity Zero’s technologies internationally (allowing other countries to further increase their own quality of life) this affords us a degree of appreciation that can work to re-solidify the United States as the center for global economic and cultural identity. Additionally, it can extend our humanitarian outreach and also lead to stronger alliances.

Scarcity Zero would have done far more for Haiti than the largely ineffective relief efforts that consumed a total of $14 billion,[19] the same with any other area victimized by natural disasters. Additionally, we maintain allegiances with other countries today based largely on inexpensive resource acquisition and the security assurances and weapons exports that come with them. But an allegiance of security is an allegiance based on fear…and fear knows little loyalty. Rather, we could create allegiances based on social and economic improvement and a functional end to the social afflictions inherent to resource scarcity and climate change. These are allegiances based on far healthier terms amid a global climate of heightened economic prosperity and easier conditions for peace.